Thomas’s mother took charge of his early education and it was apparent from an early age that he had a talent for drawing. By the age of six he was seldom without a pencil in his hand and his Aunt Elizabeth remarked on his “genius for drawing”. In fact in 1758 a family friend took a roll of his drawings to London and showed them to William Hogarth.

Hogarth was by then 61and well established and highly regarded for his prints and portraits. He is said to have thought the drawings” a very pretty performance”, but dissuaded the family from letting Thomas take up Art as a living. He said the profession was already overcrowded

This love of drawing and painting remained with Thomas all his life. He was described later as an early Impressionist having completed many landscapes and close studies of the sea, the light and clouds. Some of his work can be viewed by accessing the web site of Tate Britain where he appears in the list of artists. This gallery recently acquired one of his paintings, an £850 gift, described as “Landscape with billowing clouds”

His mother died in 1762 when Thomas was just 14. Her sister Elizabeth remained at the Hall and became an even more important part of his life.

In 1767 he took up residence in Magdalene College Cambridge. During that same year his sister Matilda married their half cousin John Kerrich, a surgeon, and went to live in Burnham Market. Thomas came home that Christmas to find his father in failing health. He returned to Cambridge but in the New Year his Aunt wrote that Samuel was very weak. A little while later Thomas received what was to be the last letter he would have from his father in which he was asked to check on the tomb of Sarah Newton his father’s first love. His Aunt must have written again for on March 7th Thomas rode through the night from Cambridge to Dersingham in an effort to see his father. He arrived exhausted only to find that his father had died shortly before.

Samuel was buried in the chancel of the church alongside his wife Barbara where their memorial tablets can be seen today. After the funeral Elizabeth left Dersingham to live with Matilda in Burnham and Thomas returned to Cambridge. William Reeve was appointed to the living in Dersingham.

Thomas graduated from Cambridge in 1771. At this time travel abroad was regarded as a very suitable way for young men of society to gain experience and improve their education. The Cokes of Holkham and the Walpoles at Houghton to name just two of the local gentry undertook the Grand Tour. As a result important collections of Art and Sculpture were established at Felbrigg, Holkham Houghton, Narford and Wolterton all important family seats established in the 18th century. So after graduation, financed by a travelling scholarship, Thomas began his tour through the Low Countries, France and Italy. He travelled with a friend, Daniel Pettiwood of Fairfax House Putney. During his stay in Antwerp he demonstrated his artistic talent by winning the silver medal at the Academy of Painting in that city.

He lived in Paris for six months and spent two years in Rome devoting his time to antiquarian research and assembling a collection of drawings of antiquities. The most celebrated traveller at this time was Thomas Coke, later to be known as Coke of Holkham. Thomas met up with him in Rome and they spent much time together. While in Rome Thomas was received by the Pope Clement XIV. He described the event to Coke in a letter in which he wrote that the Pope was an exceedingly good sort of man and very civil to the English. Apparently he considered that the English were no geese and able to speak up for themselves. Thomas and Coke met up again in Genoa and agreed to visit Milan together. However, as Thomas wrote to his Aunt back in Burnham, Coke was suffering from an ague and was unable to accompany them on all the excursions planned.

Later in 1774 they set out from Rome with 7 friends to visit Tivoli under the leadership of an English Antiquary. This trip lasted three days and began Thomas Coke’s interest in art and sculpture and his subsequent acquisitions now to be seen at Holkham Hall.

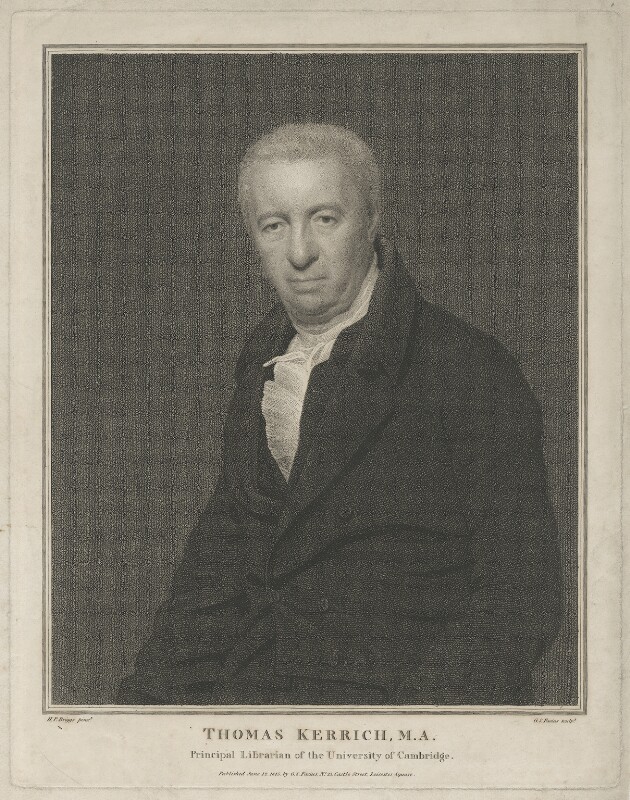

While in Rome our Thomas had his portrait painted by Pompeo Battoni the most celebrated artist of the time who was considered especially skilful at depicting English Gentlemen on the Grand Tour. This portrait is now in private hands. Thomas eventually bequeathed 26 pictures to the Society of Antiquities.

He returned to Cambridge in 1775 and gained an M.A. He was later elected a Fellow of Magdalene. A friend, William Cole, tried to persuade him to become a portrait painter but Thomas entered the Church of England and was ordained a priest at Peterborough on the 20th May 1784.

It was in 1784 that Dixon Hoste offered Thomas the living at Dersingham. From this time Thomas had to balance his duties as the vicar of our village with all the other responsibilities he took on. From 1789 to 1796 he served as President of Magdalene College. He was also appointed the principal Librarian of the University and in 1797 was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquities. 1798 was an important year for him as he became Prebendary of Lincoln Cathedral and later in 1812 of Wells. Thomas also published four scholarly papers on Gothic Buildings and one of these is still considered today as the best study of its subject.

He must have been absent from the village on many occasions. There would have been some changes to the village he knew as a child and young man. The population was still less than 500. There were still the three working windmills. One stood near where the old Railway Station was built, one at Hill House and the third at the top of Mill Road. We know from a document of 1780 that William Smith and John Stanton occupied the last named two mills. The mill at Hill House was blown down by a fierce storm in 1808.

In 1779 just before Thomas returned the village was subject to further acts of enclosure. To enclose land was to put a hedge or fence around a portion of open land and prevent the exercise of common grazing rights over it. This was done in the early centuries mainly to increase the amount of full time pasturage available to the Lord of the Manor. In the period 1750 to 1860 it was done for the sake of agricultural efficiency. In Dersingham the Little Common, Marsh Common and Badger Fen Common were subject to the Act. Badger Fen Common is that area of the common on the left as you enter the village from Lynn. The Directory records that “ 160 acres were allotted in lieu of vicarial tithes and 457 acres were enclosed within a ring fence for the use of the Parish, viz. 329 acres of marsh as stinted common and 128 acres of heath for providing whins and turf.”

Arthur Young, Secretary of the Board of Agriculture compiled a report on the effect of the enclosures in Norfolk. For Dersingham rents doubled, twice as much corn was raised, and the number of sheep increased. There were the same number of cattle as before but he maintained that the poor were not affected except by the increase of employment. Nevertheless with rents doubling there must surely have been some losers I would have thought.

Thomas became the Chief Trustee of the various charities in the village to help the poor. During his term as vicar the workhouse that had been established in the old Manor House of Westhall was still in operation. It was the 1722 Poor Law Act that stated that instead of dispensing out door relief Parishes could erect workhouses and deny aid to all who would not enter them. The “idle poor” were forced to labour. In 1732 Elizabeth Pell a member of the family who had built Dersingham Hall left land to be used here for the benefit of the poor. This land was rented out and the money received was used to buy 16 penny loaves, which were placed each Sunday on John Pell’s Tomb when it stood in the South Aisle. They were given away after the service and became known as the “Thomas Loaves”.

For centuries the tower of the church had always had a lantern with a lead covered spire rising from it in which hung a little bell. But, in 1798, the decision was taken to remove it; William Johnson received £41 17s 6d as settlement for his work on the steeple. It may have been at this time that Thomas took his pencil and paper into the grounds of Dersingham Hall and made a quick sketch of the church that he had always known before the steeple was removed. He would have been standing where there are now the woods beside Croft House.

In 1787 Matilda’s husband John died. In 1794 Thomas’s Aunt Elizabeth (Postlethwaite) died at Matilda’s home in Burnham aged 86. She was buried in the Chancel of our church and a memorial stone placed there.

On September 13th 1798 Thomas married Sophia Hayles, daughter of an eminent Cambridge Physician. They had one son Richard born in 1801 and two daughters.

During the time Thomas was our Vicar England was engaged in wars with Napoleon culminating in the Battle of Trafalgar and later that of Waterloo. These events did not go unmarked. There are many records of money being paid for prayers to be said in the church in thanks for Nelson’s victories at Saint Vincent and Copenhagen and for strength to overcome the fears of a French invasion. In the church magazine of 1899 there is a short account of the funeral of a Maria Hudson who passed away, aged 94 at the house of her son William Hudson a carpenter.

“This cheerful old lady could give her recollections of the times of the first Napoleon when inhabitants in this part of Norfolk would be anxiously looking seawards for the fleet of ships which Boney had threatened to invade England.”

She remembered that villagers had kept their “bits of silver” packed up ready to hide or carry away at a moment’s notice. Further north a lookout would be taken the last thing at night to see if fires were lighted on the beacon tower of Blakeney Church or any of the beacon hills. Maria’s gravestone can be seen beside the Church door.

In November 1807 the village was informed that 30 men were liable to be called up for service in the armed forces. Later a collection in the village raised £6.16s. 6d for the relief and benefit of the brave men killed and of the wounded sufferers in the Battle of Waterloo and in the several battles which may or may be fought in the present campaign.”

It was in 1823 that Matilda died and was buried in the chancel along side her husband John. The memorial slab can be clearly seen there on the floor to the right as you enter. Thomas himself died at his house in Free School Lane, Cambridge on May 10th 1828 and was buried in the Chancel of our church In his will he bequeathed his remarkable collection of 15th and 16th century English and European paintings to Cambridge plus the 12th century leper chapel in Barnwell near the city which he had bought and restored in 1816.

Just seven months after Thomas died his younger daughter Frances Margaretta married the Rev. Charles Hartshorne. She brought considerable wealth to the marriage and bore Charles fourteen children, four of whom died in infancy. When his son Richard died he left many of his father’s pictures including some sketches by Rubens for a set of tapestries commissioned for a convent in Madrid, to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Thomas’s wife Sophia survived him by seven years dying in Cambridge on July 23rd 1835 aged 73.

The memorial tablet to Thomas in the church, reads,” He was eminently distinguished amongst his learned contemporaries by the varied endowment of his mind whilst by the excellent qualities of his heart he secured the strong affection of his surviving family.”

So Samuel, Barbara, John, Elizabeth, Matilda and finally Thomas now rest quietly in our church with just their memorial stones to remind us of the contribution they made to this village.

George Mann

On the 22nd October 1820 while Thomas Kerrich was our vicar, George Mann, aged 19, married Maria Riches, aged 16 in Dersingham Church. They had eight children of whom one or possibly two died young. Two other sons would eventually go to live in Australia. The others stayed in this village and many of their descendants live here still. With the kind permission of the family we can follow their story and trace the history and development of Dersingham through the 19th and 20th centuries.