1643

The whole of England was in a state of intense anxiety. The relationship between Parliament and the Crown had finally broken down and England was at war with itself, county against county, town against town and father against son. The King had left London and established his court and Capital in Oxford changing that comfortable University City into a garrison town needing strong fortifications.

The first battles and skirmishes had been fought and news of them had been spread by word of mouth but more tellingly by the publication of numerous pamphlets. The siege and battle at Newbury in July 1643 was vividly told. There were heavy losses reported on both sides and ”the soldiers having almost starved the people where they quarter and are half starved themselves, and for want of pay are become very desperate ranging about the country breaking and robbing houses and passengers and driving away sheep and others cattle before their owners faces.”

Far worse was to be reported. During Christmas time that year at the village of Barthomley in Cheshire the villagers had taken refuge in the church steeple when the King’s army approached. The soldiers set fire to the pews to force the villagers down, whereupon they were ”barbarously and contrary to the laws of arms murdered.” Many stories of murder, destruction of houses, and all manner of mayhem and atrocity were reported from both sides. However there was an even greater fear than that of the behaviour of the armies. The fear of papacy was paramount.

The King’s wife Henrietta Maria was viewed with absolute distrust. She had had a chapel built at Somerset House where she and many of the aristocracy at court heard Mass. As a practising Roman Catholic she was suspected of trying to persuade the King to convert to her faith. After all she had refused to attend his coronation, as it was a Church of England ceremony.

The people had grown accustomed to the plain white walls, bare wood, and order of service in their churches introduced during the reign of Elizabeth1. When Archbishop Laud began trying to bring back some ceremonial in the form of altar rails, reverence for the Eucharist and robes for the Ministers it caused great alarm to the Puritans or ”the godly” as they thought of themselves. It was rumoured that a papist army was lurking in South Wales just waiting for the right moment to invade. A poor man, Thomas Beale, stated that while he was lodged in a ditch near a Post House he heard two men planning to surprise and take London. Catholics were rumoured to be amassing supplies of gunpowder to blow up the chief cities of England. There was no real evidence that Catholics had any such intentions but rumour fed on rumour.

So in this highly charged atmosphere what was happening here in Norfolk? If we coloured a map of the country in the way that is done during General Elections now to show party gains and losses East Anglia would be coloured solidly for Parliament. It was called The Eastern Association. Nevertheless there were many royalist supporters and Roman Catholics in the area. In January 1643 Cromwell and his troops swept through Norfolk arresting anyone who did not fully support Parliament. Moreover war is an expensive business. Armies have to be equipped, fed and housed so County Committees were empowered to raise money by taxing their populations, or sanctioning compulsory loans. Money, silver plate, arms, horses and men were all expected to be offered for the support of Parliament.

In Dersingham Sir Valentine Pell lived in his family’s large house built in 1553 about where the surgery now stands. (Dersingham Hall and the Tithe barn had yet to be built.) He was a Puritan and staunch Parliamentarian. He had been appointed to take over a company of foot previously commanded by Nicholas L’Strange of Hunstanton.

The L’Stranges of Hunstanton Hall were Royalists and had openly declared their support for the King. Dersingham in fact was surrounded by families who were Royalist supporters and many also Roman Catholic.

William Cobbe of Sandringham. a considerable landowner in the village, was known to be Catholic. His estates were sequestered and he had to heavily mortgage them in order to have an income while he was so highly taxed. He was a Colonel in the King’s army and was married to a daughter of Sir Henry Bedingfeld of Oxburgh the leading Royalist and Catholic in the area.

A member of the influential Paston family, William who lived at Appleton Hall just beyond Sandringham, was a noted recusant and Royalist. (Appleton Hall no longer stands unfortunately.) The Hovell family at Hillington, and the Yelvertons at Grimston, were both Catholic and Royalist. Many older villagers would still remember Henry Walpole of Anmer Hall, who became a Jesuit priest and was tortured horribly in the Tower before being executed in 1595.

So the fears of a Catholic plot to overthrow the present order would have been very relevant here. Parliament was well aware of the situation. As with other Royalist families in the area the L’Estranges were ordered to surrender all arms and ammunition at Hunstanton Hall to the magazine at King’s Lynn. Armed guards were maintained day and night on all the bridges and ferry crossings between Cambridge and Lynn to intercept men, horses, or plate being sent from Norfolk to the King. Parliamentary ships patrolled the Wash to safeguard the strategic port of King’s Lynn.

Then in August 1643 Sir Hamon L’Strange mounted a successful coup in Lynn and declared the town for the king. This brought the Earl of Manchester, Captain-General of the army in East Anglia, hot foot to the town. Advanced parties of soldiers secured all the roads into Lynn and security in The Wash was increased. The sound of the daily canon fire into the town could be heard and people living in Gaywood fled from their homes into the surrounding countryside. They would all have heard the rumours of what happened when soldiers came to your area.

I do not know if Sir Valentine’s foot company were involved in this particular operation but he and his troop, some Dersingham men must have been included, were active during the campaigns. It was at this time that the hoard was buried which was frequently the only way of safekeeping valuables. It was on land belonging to Sir Valentine but it is unlikely that he or a close member of the family was responsible.

Although a considerable amount of money for that time it was still not a large sum for a prosperous landowner. The cup was damaged and unlikely to be a prized possession in the Pell house. Moreover he was on the winning side, and lived to 1658 so would surely have recovered it. Parliament at the time was seeking subscriptions of money and plate and a damaged piece for scrap silver plus the coins would have been a reasonable amount. A strong incentive for the owner to hide it.

It has been suggested that it was loot damaged in the taking and the looter never returned. There is not much evidence however that looting took place even after the surrender of Lynn. It could have had a connection with the church. Spoliation of churches and Priest’s houses during the rooting out of insufficiently Puritan clergy did take place but nothing certain is written about what happened in Dersingham. The church plate seems to have survived the iconoclasm of the time and the church already had a communion cup from Elizabethan times and was unlikely to have added to it.

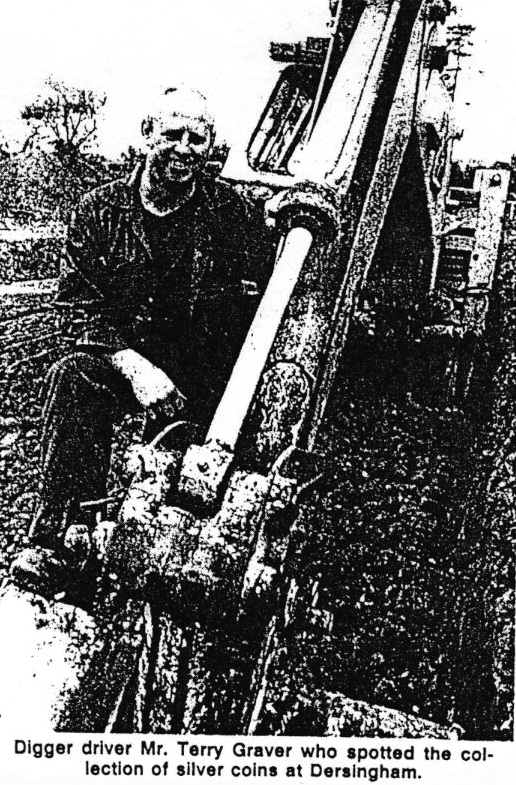

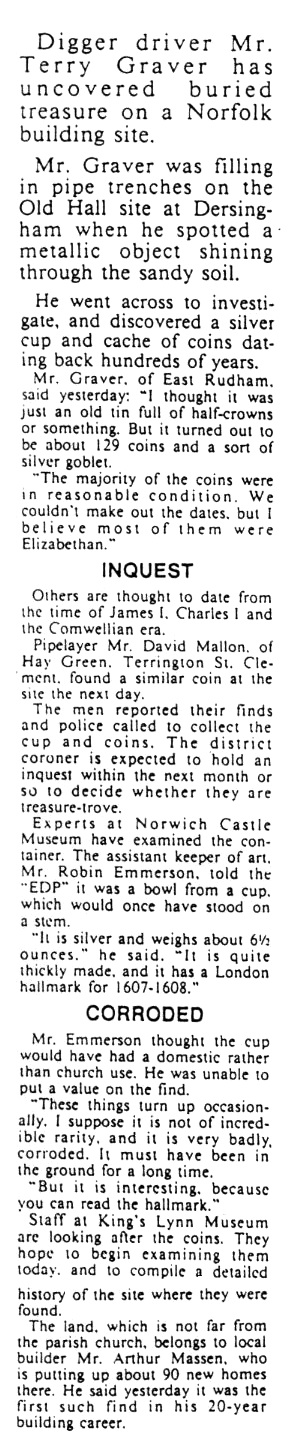

Of course it might have been military pay rather that loot. Someone however, in the highly charged atmosphere, of the time went out one night onto Pell land. They must have chosen a landmark of some kind to aid easy recovery then quietly dug a deep hole and placed their treasure within it. They told no one of its whereabouts and for reasons we can only guess at never returned to retrieve it. If it was a villager hiding his savings then not even family members knew where it lay for the next pair of hands to lift it out of its hiding place were those of Terry Grover in 1984. It was declared Treasure Trove in 1985 and purchased for the Lynn Museum with a grant from the V&A museum. Mrs Elizabeth James, curator of King's Lynn Museum is pictured here (left) with three of the coins.

Mr David Mallon (below) found another coin the day after Terry Grover's find.

Below is the original Eastern Daily Press newspaper article, which we wish to acknowledge as owner of this work, and Elizabeth James, Museum Curator.