The fen was completely open, there was no obstruction right across to the hills that led down to Wolferton Station. The remains of the old firing range were there, the butts that held the targets and a barrier of brush and sand that stood behind it, in case a stray bullet might have reached Wolferton. The firing positions were rotting away, and the whole area was very flat and covered with patches of white sand and rough marshy growth.

When I was transferred to the grammar school at King’s Lynn, this of course entailed a daily trip on the train and arrangements had to be made for a lunch. A small group of us – not all from Dersingham but from the Heacham, Hunstanton and Snettisham area – travelled on the train. Some took their lunch, but an arrangement could be made with Ely’s restaurant on Norfolk Street for a boy’s lunch for a shilling a day. Ely’s restaurant was on the left-hand side of Norfolk Street, probably 8 or 9 shops up from the High Street. We were given a very reasonable lunch, sometimes sausages and mash, sometimes pieces of beef, whatever was on the menu for the day. Except on Tuesdays. Tuesday was market day, and we were relegated to an upstairs room with the hired hands of the farmers and dealers and other people who occupied the main eating rooms downstairs. The service up there wasn’t very great.

After the lunch – we generally had about two hours for lunch at the school – we would wander through the Market Square and past the Globe Hotel, down the the quays. In February, of course, Lynn Mart was in full swing and I am afraid there were times the shilling we were given for our lunches was spent on the attractions of the Mart and on Thurston’s entertainments.

On long summer evenings, we often on a Sunday would take a walk. This would involve Mother and myself, my sister, and visiting aunts and uncles, whoever in the family who happened to be living with or visiting Grandfather at the time. One of the favorite walks we had was across the common, towards Sandringham. After passing through the little wood – that was the area between the common and the Princess’s Drive – we would walk along the Princess’s Drive towards Wolferton. Now the Princess’s Drive – it is rapidly today being obliterated and overgrown –started at the top of Sandringham Hill, and ran along the crest of the hills overlooking the fens and marshes, until it exited at the Wolferton Road. It had been constructed quite early in the Prince and Princess of Wales’ residence at Sandringham and at that time a number of overlooks had been cleared through the trees so that there were excellent views across the fens and marshes to the distant Wash. At the time we would make walks along there some of the overlooks were being overgrown.

Just after you left the entrance to the Drive at Sandringham Hill you came to the home of Mr and Mrs. Boughen and their son Leslie. Mr. Boughen was the estate’s forester.

Somewhere along the Drive toward Wolferton and standing a little back from the road there was a fine stand of edible chestnuts. I can assure you we raided them regularly in October. They weren’t great big chestnuts, but they were sweet little things with a very spiny outer cover.

There were occasions we – that is my mother, my sister and myself – would visit Grandfather at his office at Sandringham House. Sometimes when his duties did not allow him to get home every evening – perhaps this would happen on a weekend – Mother would say “Well, we’ll go to visit Grandfather today.” We would walk up across the common and through the woods, and up to where the memorial is, and then walk along the road and past the Norwich Gates until we came to the entrance to the back of Sandringham House. I don’t really remember much about Grandfather’s office. He had a little living room beside it where he could stay at night. We would always end up being taken into the servants’ dining room to have a little light refreshment. Here I met a number of the senior servants of the household, but I only remember Miss Noon, who was the housekeeper, by then a rather stately and middle-aged lady, in fact probably quite an elderly lady. Ultimately, after the death of Queen Alexandra in 1925, she was put in charge of York Cottage in a form of semi-retirement. We visited her there once or twice but it is not something I remember very much about, except that she had a young lady who looked after her requirements – and ours – and served us whatever refreshments were offered.

As members of Grandfather’s household, we were invited to the Christmas tree and celebrations that were given for the staff. I think we attended that function in 1923 and again in 1924. There wasn’t one in 1925 because Queen Alexandra had died. I still have in my possession a small doll that was given to my sister Catherine at one of those functions and a permanent desk calendar that was given to my mother. We conveyed to Sandringham probably by Mr Hyner’s taxi, because it was wintertime, and refreshments would be served. Finally we would assembling the ballroom. A huge Christmas tree would be standing in the middle, all lighted up. We stood around in a huge circle around tables, and a present was found for each one of us. We had a number, and when the number was called we would indicate where we were, and one of the members of the Royal Family or the Household would come and present us with this present. Of course we had to be very polite and say a very nice thank you.

The highlight of the Sandringham year of course was the flower show. It was held toward the end of August every year, just adjacent to the church. This was a highlight, not so much for the flowers, from a boy’s view of it, but for the opportunity to sneak into the grounds of the House itself. We would then go around to the back of the lake and climb up into the little summerhouse that overlooked the lake. This had been built by the King – the Prince at the time – for Alexandra and was lined with blue Danish tile. He had built it just to remind her of her Danish homeland.

Even after the flower show was over, we could sneak into the grounds through the gates, because they were open. I’m not sure quite how we did it, but Raymond and I were able to find a way into the grounds to sneak up and play around that summerhouse. We did it quite a number of times and were never intercepted or challenged.

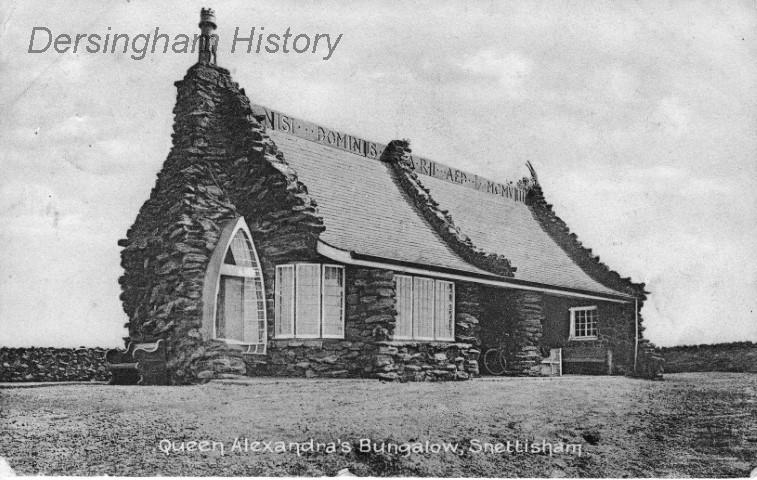

Now I will turn my attention to Snettisham Beach. In 1908, or maybe 1905, Grandfather built a summer cottage, always called the bungalow in the family, on the shingle ridge overlooking the Wash, in sight of the end of the road to the beach. Before the development of cottages along that stretch of beach there had been a number of huts. Most of these, I think, had been day huts, because the beach, in the late Victorian period and through the Edwardian period, had remained a popular watering place for the villages of Snettisham, Dersingham, West Newton and Wolferton, etc. As far as I know, only one of these huts was used year round. I will come to that in just a minute.

The road to the beach started in Snettisham and ended at the beach; it passed over the shingle ridge and down onto the cockle flats. These were beautifully clean sandy flats and were used for both commercial cockle gathering and for those people who went out to gather them for their own use, which we did frequently. There were two or three other beachfront cottages built at approximately the same time as my grandfather’s; the first one was owned by a family named Knight. It was later sold to a family named Spaulding. Next to it was an inhabited hut lived in by a man named Bob Pepys. Bob Pepys was a year-round resident of the beach. He lived by gathering cockles, gathering mushrooms, acting as a refuse removal man for the cottages that were being developed, and by beachcombing and by whatever odd jobs he could get. He did some of the shingle work as well. Next to Bob Pepys was Grandfather’s cottage; the next one to that was owned by the Insley family of Dersingham. I think that was probably all the cottages that were built before the first world war. There may have been one or two others.

When the First World War came, within a matter of days an officer turned up at the house at Dersingham and demanded the keys in the name of the King. It was August, and the cottage was furnished; all the bedding and flatware and dishes were in place because this was the holiday season. The members of the family were certainly expecting to use it. However, it was requisitioned, and Grandfather was not allowed to go to remove anything. It had to be exactly as they took it over, and they took it over within days of the outbreak of war. It was returned to Grandfather shortly after the Armistice in 1918, but, oh dear, the interior had been absolutely, totally wrecked. Everything that could have been broken up and burned had been, the tables, the chairs; the bedding and sheets had been stolen or destroyed; the cutlery, the crockery – just everything that could have been smashed or broken had been done so. Really, the bungalow was just an empty shell, and as far as I know no recompense or restitution was ever made. From photographs that I have, we were back into the bungalow in the summer of 1919. Some considerable refurbishing had taken place by that time.

.jpg)

b.jpg)